By Christine Stenner, Attorney (Germany) at Stenner Law| Foreign Legal Consultant (PA) | November 9, 2025

The night of November 9, 1938—known as Reichskristallnacht or the “Night of Broken Glass”—marked a horrifying turning point in Nazi Germany. Across Germany and Austria, Jewish homes, synagogues, and businesses were attacked, looted, and destroyed. Windows shattered, Torah scrolls burned, and families were terrorized. It was not a spontaneous outbreak of anger, but a state-orchestrated pogrom that revealed how far Nazi antisemitism had progressed since Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1933.

When Hitler became Chancellor in January 1933, antisemitism was already central to Nazi ideology, but it had not yet taken the form of mass violence. The early years of Nazi rule focused on exclusion, propaganda, and legislation designed to isolate Jews from German society. The Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service in April 1933 expelled Jewish professionals from public employment. Other decrees barred Jews from schools, the press, the arts, and public life. Boycotts of Jewish-owned businesses, such as the April 1, 1933 campaign, were early signals of what was to come.

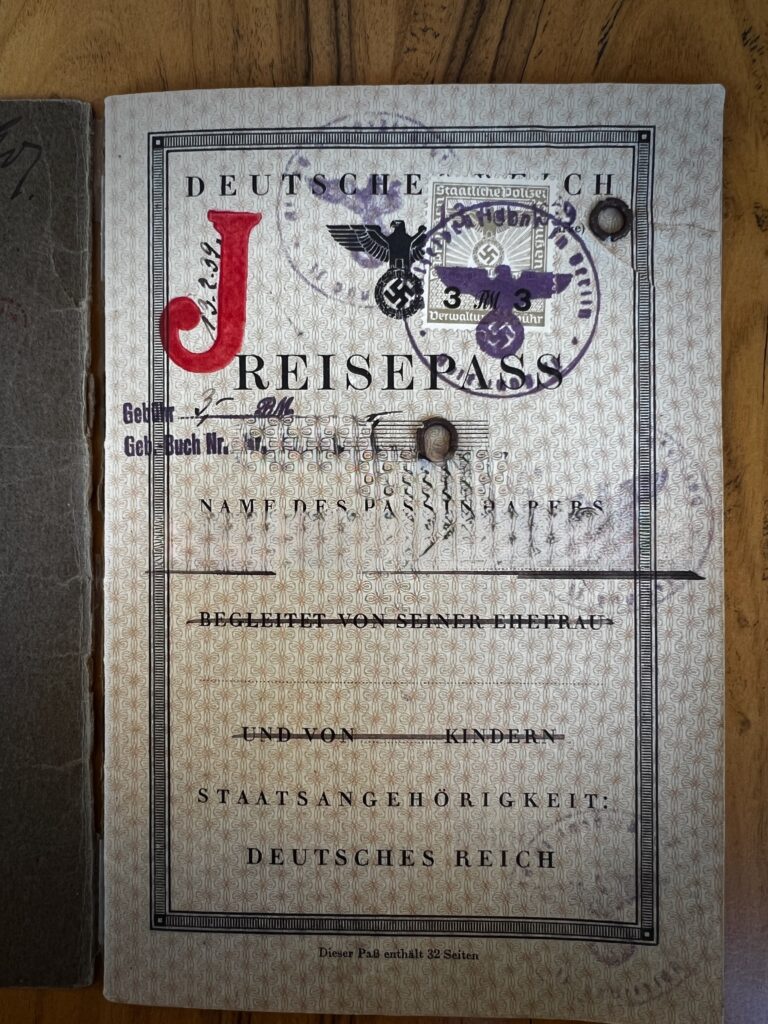

The Nazi regime systematically used law and propaganda to reshape society’s moral boundaries. Through the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, Jews were stripped of citizenship and forbidden to marry or have relations with non-Jewish Germans. The laws institutionalized racial definitions, turning prejudice into state policy.

As a German citizenship lawyer, I often hold the original documents from that time in my hands—birth certificates marked with “Israel” or “Sara,” confiscation orders, or passports branded with a red J so border officials could identify their holders. Each piece of paper tells the story of a life upended, a family forced to flee, and a nation that turned its own citizens into outcasts through laws that began with words and ended in persecution and violence.

Each of these cases is a reminder that what happened on November 9, 1938, was not inevitable—it was allowed. Remembering Reichskristallnacht is more than an act of mourning; it is a vow that the machinery of hatred and exclusion must never again be permitted to rise unchecked.

About the author

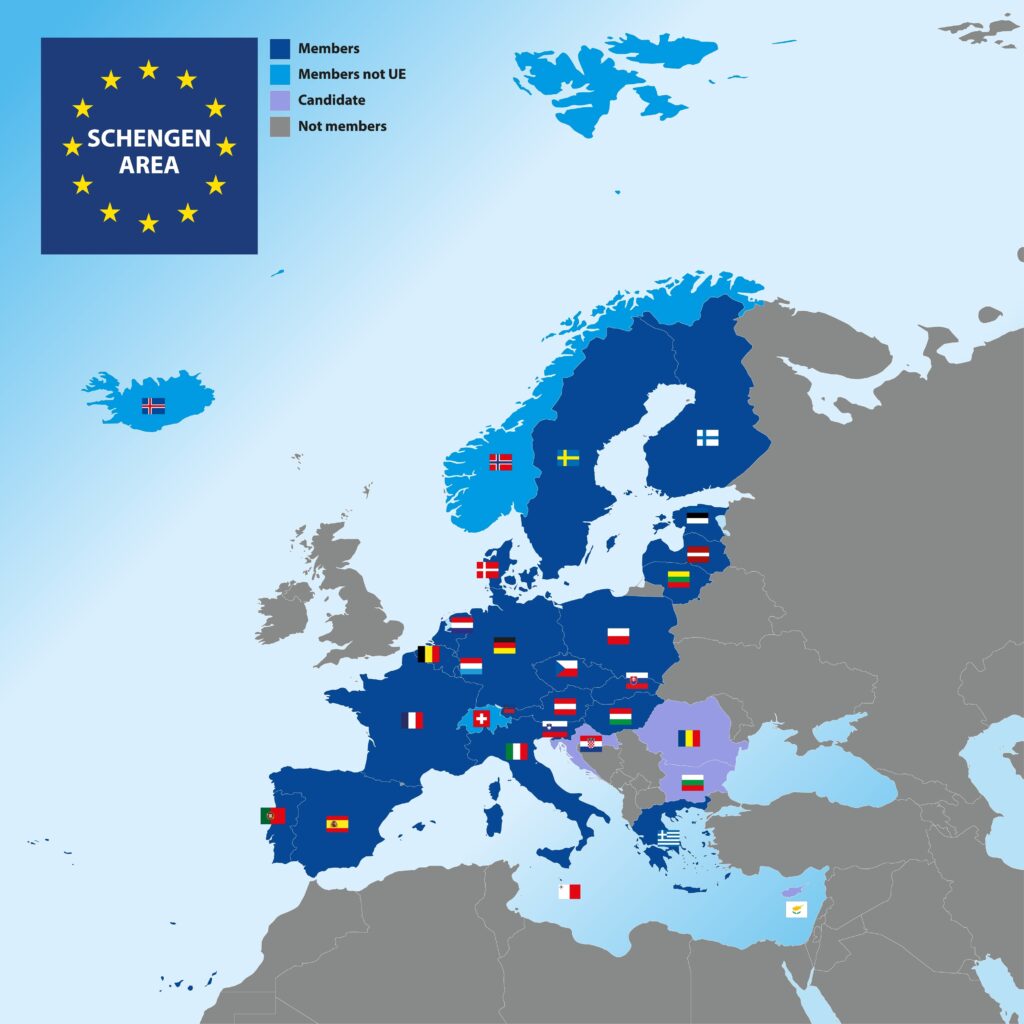

Christine Stenner is a German attorney with 25+years of experience. She is admitted to practice German law in the United States and focuses exclusively on German citizenship law for clients living abroad. At STENNER LAW, she assists applicants with restoring or reclaiming German citizenship through declaration, re-naturalization, and restitution-based applications.